Electric Vehicle Stats, One Year In

One for the EV and data geeks out there: an analysis of charging and performance history

When I last wrote about my experience with an EV, I had only been driving electric for a few months. I found myself right in the honeymoon period of new technology adoption. I had great things to say back then.

Today, after a full year of being immersed in a new way of driving, I am older and wiser, and I have the data to prove it. My younger and more naïve self of nine months ago painted a rosy picture of electric vehicles as being superior in just about every way to the “noisy and clunky explosion-propelled polluting machines.” Have my views changed?

In short, no. Electric vehicles are better products by almost any measure. They are still the future. Rather than restating my subjective opinions, though, this time I’ll let the data do the talking.

I crunched the numbers for every charging session over twelve months of EV ownership, layered with temperature data at the time and location of charging, monthly odometer readings, and my electricity bills, to give me a comprehensive picture of EV performance across range, charging, and financials.

Having all this historical data available for analysis is yet another advantage of EVs. Instead of relying solely on the car’s odometer and an imprecise fuel gauge, I know exactly how many kilowatt-hours were loaded into the battery in each charging session, detailed stats of the sessions themselves, where the vehicle was at the time of charging, as well as the conditions around it. Or does your local gas pump have an API too?

The usual caveats apply: this analysis is solely based on my own car (a 2022 Hyundai Ioniq 5 AWD), my driving habits (mostly local, punctuated by long trips, and no daily commute), as well as the location and climate I live in (Boston, MA; great summers, miserable winters). This is my data and my particular reality. However, from what I know about other EV owners out there, my insights are representative of the electric car adoption experience, at least in the United States.

While these insights are by now common knowledge, it is cool to be able to surface them with actual data, and for my own vehicle to boot. What the data shows:

Driving electric is much cheaper

Range decreases significantly in the winter

Charging performance also drops when it’s cold

Charging at home is cheaper, mostly

Electrify America has been somewhat disappointing

Let’s dig in.

The cost of driving an EV is nearly half that of an ICE

The fuel for the 13,277 km of mileage over the full twelve months cost me a total of $202, most of it through my electricity bills for charging the car at home.

Plugging in at Electrify America (EA) won’t cost me anything in the first two years, a deal between EA and Hyundai that has already saved me more than $500 and counting in discounted charging fees.

As a benchmark, had I charged my car exclusively at home, the fuel cost during the first year would have been $695. While that scenario is not quite realistic (a longer trip means charging on the road), it does tell me that annual fuel costs should hover around $700, significantly lower than the $1,328 that the same mileage would have cost me in gasoline with my previous car, a Mazda CX-5 that ran at an average of 10¢ per kilometer driven at the current price of gasoline.

The cost of EV charging does rely on the price of electricity, which is on the expensive side where I am at around 30¢ per kWh. However, price volatility is minimal compared to gasoline prices that are increasingly exposed to developments in geopolitics. Cheaper, check. More predictable, check. A deal that will save me $1,000 over two years, check.

Range efficiency drops by 30% or more in the winter

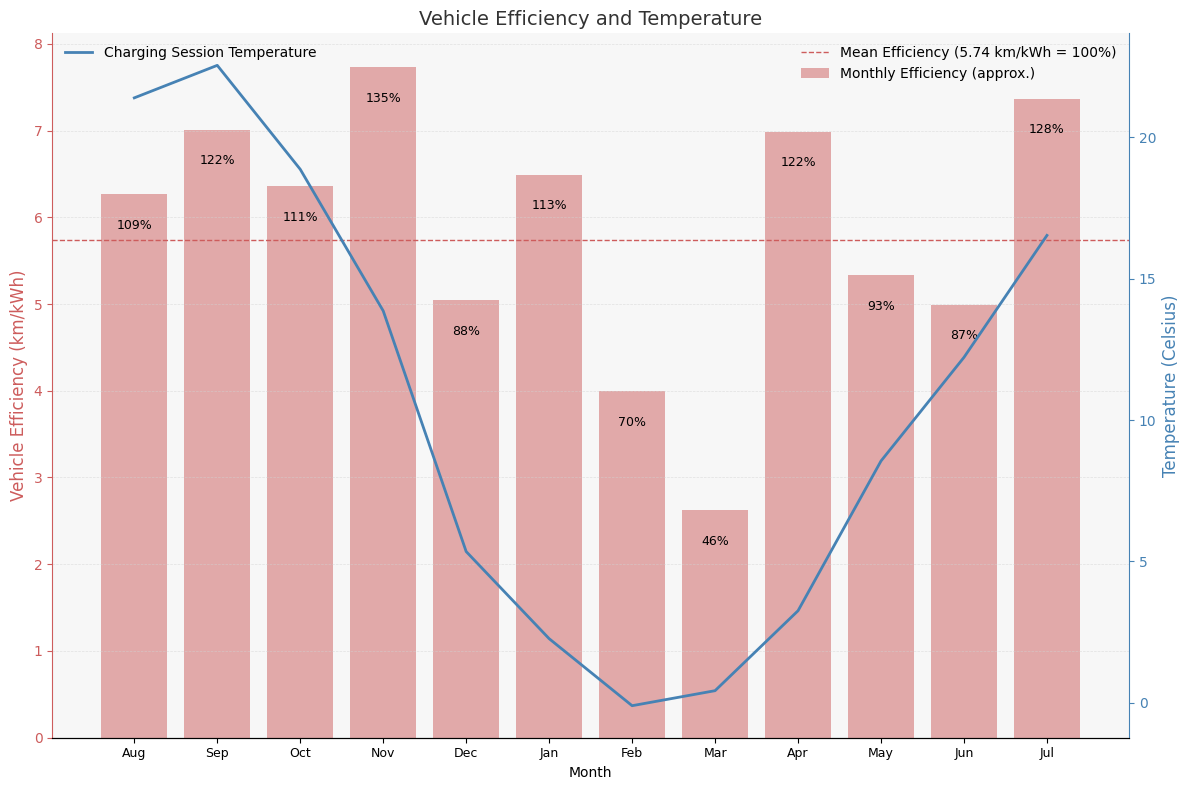

Dividing the odometer reading by the total amount of energy delivered to the battery gives me the range efficiency for the year: 5.74 kilometers per kilowatt-hour.

I was surprised to see better performance than the 5.5 km/kWh I had estimated after three months of driving exclusively in mild weather, before I had experienced any impacts of winter.

Below I plotted the monthly range efficiency and deviation from the mean of 5.74 km/kWh, along with the average temperature.

Note that I am plotting the average temperature during the charging sessions rather than the actual average temperature for the month. I ran out of time to build a more comprehensive temperature dataset. Still, it is good enough for my purposes here.

The monthly efficiency numbers are also imperfect. I am simply dividing the number of km driven each month by the energy delivered to the battery in that month. Some of that charging took place at the very end of the month, which means the bulk of the energy was actually consumed in the following month. That is why the bars are spiky, but it is still a good approximation.

Regardless, the impact of temperature on range is clear: in the winter, performance drops by 30% or more, and in the shoulder seasons it is up by 20% to 30%.

Temperature also impacts the maximum charging rate

I wanted to visualize more detailed charging performance data alongside the outside temperature for each session. In the following chart, the green bars represent the sessions at Electrify America’s DC-charging network, and the orange bars depict home charging sessions with the Level 2 ChargePoint in my driveway.

The bubbles show the maximum rate of charge reached in each session. The Ioniq 5 sports a very fast 800-Volt platform. Hyundai claims it can take advantage of the fastest chargers to deliver about 55 kWh to the battery (from 10% to 80%, or well over 300 km of range) in just 18 minutes. Unfortunately, with Electrify America’s ultra-fast units still few and far between, the locations most convenient to me are capped at 150 kW. Even when I did get to their 350 kW chargers, I never saw the rate tick above 175 kW. To be clear, that is already a pretty fast rate, adding considerable range in just 15-20 minutes.

The performance of my home Level 2 charger is mostly constant, regardless of weather or vehicle conditions, so it is less interesting for this analysis. Instead, I plotted a best-fit curve for the maximum charging rates at Electrify America only.

In the first few months, I consistently saw a high rate of charge at or above 150 kW. As expected, performance dipped considerably as the weather cooled, down to less than half the top charging rates I had experienced in late summer.

However, as the weather improved, I failed to see the a return to a great charging performance at my local DC charging station. This can be clearly seen in the chart, where the lines for temperature and max charging rate diverge in late spring. The reason, I suspect, is that Electrify America has been capping the charging rates at several stations, including my local charging spot, while extensive infrastructure upgrades are carried out. As a result, I rarely see rates above 70 kW anymore, even in perfectly mild weather.

Here’s another view showing the EA cost per kilowatt-hour going up in warmer months when it should be going down.

Charging at home is usually cheaper

Because EA in Massachusetts sets their pricing by the minute rather than by the kilowatt-hour, the cost is higher in longer charging sessions, which happens often in low temperatures.

The green trendline below shows a somewhat weak but definite correlation between temperature and cost of energy. Even if EA costs vary significantly between sessions, things do trend cheaper at higher temperatures. Very fast chargers can bring the cost of energy well below what I pay at home. However, unless EA can deploy better infrastructure, once I have to start paying them it will be, on the whole, cheaper to just plug in at home — and more convenient, too.

Another version of the same chart shows a stronger correlation between charging speed and temperature, where the more expensive sessions (larger bubbles) tend to be slower.

I love it how both charts illustrate how constant the performance of the Level 2 charger is. It might be significantly slower, but once one gets into the habit of plugging in every night at home, the “tank” is always full each morning.

Today’s resource is: GPT-4

I had a blast doing this analysis with help from ChatGPT’s code interpreter. I hadn’t written proper code in many, many years, but the AI made it all so easy.

I got to focus on describing what I wanted to achieve at every step in the analysis, while the AI took care of producing readable and elegant code. Over spare hours here and there I got it to clean the data, merge multiple datasets with charging history, odometer readings, electricity bills, plus fetch geolocation and temperature data using publicly accessible APIs, help me with troubleshooting, and finally plot useful and visually appealing charts. I just had to make some tweaks and keep the AI from going down unproductive rabbit holes.

GPT-4 made coding fun again.

The experience I had collaborating with the AI matches this discussion very closely: