Keep the Coal in the Ground. We Might Need It One Day.

Vast reserves of easy-to-access fossil fuels are our insurance policy in the event of a worst-case scenario for civilization

Lately, I’ve been quite absorbed by longtermism, a philosophical perspective that emphasizes the importance of valuing the far-reaching impacts of our actions on future generations.

It is common sense that everyone wants to make the world a better place for their children’s and grandchildren’s generations to live in. In contrast, the concept of caring for people who don’t yet exist and might not exist for thousands or even millions of years doesn’t come naturally to many. Yet, it is also common sense.

Future people, after all, are people. They will exist. They will have hopes and joys and pains and regrets, just like the rest of us. They just don’t exist yet.

Think of something you love in you own life; maybe it’s music or sports. And now imagine someone else who loves something in their life just as much. Does the value of their joy disappear if they live in the future?

Imagine what future people would think, looking back at us debating such questions. They would see some of us arguing that future people don’t matter. But they look down at their hands; they look around at their lives. What is different? What is less real? Which side of the debate will seem more clear-headed and obvious? Which more myopic and parochial?

These are some of the arguments made by Scottish philosopher William MacAskill in What We Owe the Future, a treatise on longtermism. Among discussions such as the likelihood that humans will go extinct this century, or whether a long future for civilization is a net positive, MacAskill explores the topic of collapse; the idea that civilization as we know it could end due to an event that wipes out something like 99% of the global population, such as a massive asteroid collision or an all-out nuclear war. The chances of such an absolute worst-case scenario are exceptionally low, but they’re not so improbable as to be entirely comforting. In fact, over a very long period of time, the probability of a black swan event of disastrous proportions becomes increasingly high.

While we need to do all we can to avoid a collapse of society, we must also recognize that it could happen, and take all the steps necessary to increase the chances that those who survive can rebuild civilization.

I often encounter a point of view that goes something like this: “Well, if we screw up that badly, then we deserve to go extinct.” I think this is wrong for at least two reasons. First, even a human-caused catastrophe like a nuclear or biological war would be the doing of a miniscule portion of the global population, and it doesn’t follow that billions of people should have to pay for the misdeeds of a handful or even a few thousand individuals. And even if that were the case, such a disaster would certainly not be the fault of future people. Just like people in the past have made things better for us, we owe the same to those in the future.

(I cannot do justice to a proper exploration of longtermism here, and I won’t try. I can recommend this article. Even better, read MacAskill’s book. Now, back to the show.)

Because a civilization collapse could wipe out a great deal of knowledge and technology we take for granted today, society could be thrown back to pre-industrial times, losing all ability to create modern technology. In order to reindustrialize, the main bottleneck would be energy.

Harnessing energy would be incredibly challenging in a post-collapse world. Extracting fossil fuels such as petroleum and natural gas, or generating electricity from the clean sources powering today’s energy transition, requires advanced technology and international supply chains. We could not hope to operate complex power plants, so nuclear power and probably big hydro would be out of the question. Any remaining solar and wind farms would continue to work for a while, but they cannot generate the high-temperature heat needed for industrial processes. And renewables would not last long because their lifespan is short; without the ability to manufacture high-tech solar PV cells or plastic composites we would run out of large-scale solar and wind power in a few decades. Artisanal methods of extracting some energy from rivers, wind, and wood would remain, but in order to undergo a new industrial revolution, our unlucky survivors of the future would need coal.

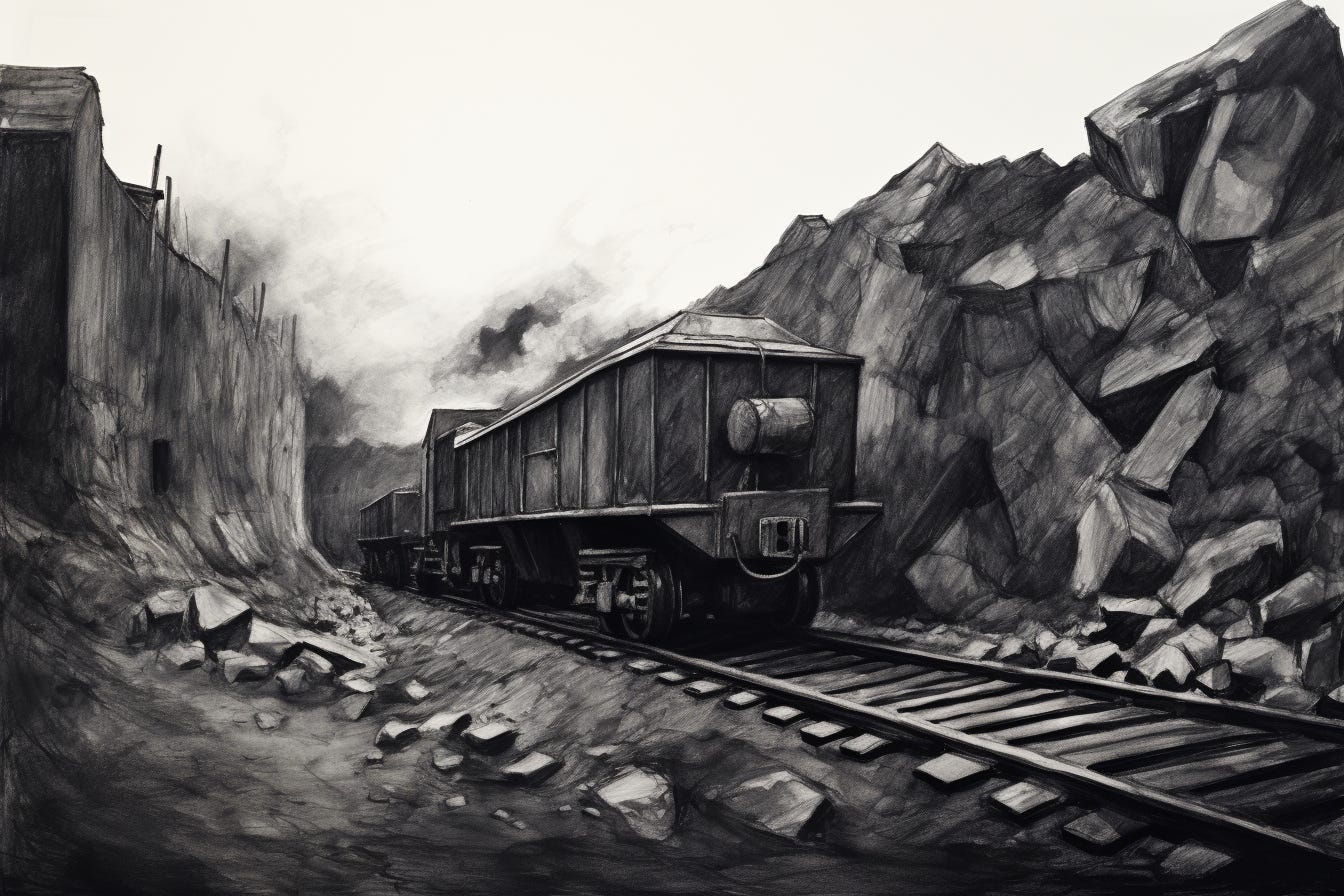

Coal is an extraordinary thing

Let’s take a minute to marvel at how amazing fossil fuels are.

Most of the coal in the Earth’s crust dates from the Carboniferous period, a brief span of time (geologically speaking) about 300 million years ago, when vast forested areas got trapped under water, buried in mud, compressed, pressurized, and heated until plant matter transformed into a black rock rich in hydrocarbons. I think of coal as nature’s long-duration solar power storage.

Coal packs a lot of energy. A single kilogram can yield up to 8 kWh of energy, enough to power around six hours of electricity usage in the average U.S. household, or to drive my car for 40 km.

Easy-to-access coal near the surface gave humanity a leg up in modernizing. We could dig it up and burn it to release copious amounts of energy. Initially, it was particularly useful for generating the high-temperature heat essential for making cement, steel, brick, and glass. Before the mid-1800s, the only alternative to coal was biomass: wood, crop waste, and charcoal. Biomass is energy-dense too (some advanced industries still use it), but the extensive land requirements put it in competition with agriculture, which means humanity could never power an industrial revolution while simultaneously growing in population. The land-use math just doesn’t add up.

Once dug up, coal could be moved to where it was most useful: powering factories and large population centers. Provided you could transport it and store enough of it, coal was an effective way to power a city or a country, every hour of the day, every day of the year. It was our first source of flexible, dispatchable, reliable, transportable, and dense energy at scale.

We would not be where we are without fossil fuels. If you are reading this, you have an internet connection. You can make the lights go on right now by flicking a switch on your wall. You can turn a dial in your kitchen to produce controlled fire on command and prepare a hot meal in minutes from ingredients in a cooling box that keeps your food fresh for weeks. You have robots in your house that wash and dry your clothes and your dishes. You have healthcare workers, firefighters, and police officers on standby in case you ever need help. You can fly anywhere in the world in a matter of hours. You have access to more knowledge at your fingertips (quite literally!) than any other human being who has ever lived. You can take a short ride to the nearest supermarket and purchase just about any kind of food from anywhere in the world at any time of the year.

We are living in the future, and every single bit of it was made possible by an industrial revolution powered by coal.

Alas, there is no such thing as a free lunch

As it turns out, our habit of burning stuff to make energy has downsides. Despite having fueled the astonishing human and technological advancements of the last two hundred years, the use of fossil fuels, and coal in particular, releases a massive amount of pollution into the environment.

In the mid 1900s, fossil fuel pollution began to envelop the world’s largest cities in a hazardous smog. The solution at the time was to move coal plants away from large population centers. As the world developed, we built more coal plants, mostly out of sight and out of mind.

Today, however, we understand that the full scope of the damage extends far beyond air pollution in our cities: dangerous warming of the climate on a planetary scale is well under way, we are causing it, and it all began with coal.

Despite all the progress we’ve made in addressing climate change, coal is still the most widely used energy source, supplying more than a quarter of the world's primary energy and over a third of its electricity.

And there’s plenty more to burn. As MacAskill points out, the world has an estimated “twelve trillion tonnes of carbon remaining in fossil fuel resources, of which 93 percent is coal.” Even if only a fraction is ultimately recoverable, burning all of it would tip the climate well past the worst-case scenarios being modeled today, which would be very, very bad. To be clear, that is not the path we are on today, thankfully.

Could we rebound from collapse?

Historically, no countries have ever developed without fossil fuels, and few have done so without coal.

On the path to industrialisation and out of poverty, countries begin by burning prodigious amount of fossil fuels, usually, though not always, starting with coal and then shifting to oil and gas.

That’s not to say that development can’t happen without fossil fuels today. The landscape is entirely different in modern times. We now have clean energy technologies that can enable countries to grow and pull their citizens out of poverty with little fossil fuel use, and that will increasingly be the case over the next few decades.

The question posed in the context of longtermism is a different one: should civilization collapse and have to start from scratch, could it recover without easily accessible fossil fuels? As we saw earlier, it seems rather unlikely that it would, given how inaccessible other forms of energy would be to a post-collapse society regressed to pre-industrial technology.

We would need plenty of coal to get us to a point where we could again transition to high-tech clean energy. By leveraging the deposits available today, that would still be feasible.

How much coal is left?

There are an estimated 200 billion tons of carbon remaining in surface coal reserves. Coal is abundant and well-distributed throughout the planet, so the largest reserves tend to be located in the largest countries: China, the United States, India, Russia, Australia. The largest coal mine in the world, the North Antelope Rochelle in Wyoming, U.S., has about 900 million tons or carbon in near-surface coal. Here’s MacAskill again:

This single mine alone could fuel the first few decades of reindustrialisation. The amount of surface coal remaining worldwide would be enough to provide all of the energy we used between 1800 and 1980.

However, today we are still burning coal at an eye-watering and planet-warming pace, and we won’t have much left if we keep at it.

Since, historically, the use of fossil fuels is almost an iron law of industrialisation, it is plausible that the depletion of fossil fuel could hobble our attempts to recover from collapse.

A net-zero world might still deplete coal reserves

Even in a successful transition to clean energy, fossil fuels will still be needed in hard-to-decarbonize sectors and as raw materials for things like plastics. Hopefully we can restrict sources to oil and gas only, and stop using coal altogether as soon as possible. Even then, arriving at a clean energy economy by using the wrong technology mix could backfire in the long term.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS), where some of the pollution is prevented from reaching the environment, and carbon dioxide removal (CDR), where carbon is pulled from the atmosphere, will be important technologies to reach net-zero. In fact, the scientific consensus today is that they will be essential.

Paradoxically, an extremely successful development of CCS and CDR technologies could be harmful, as it would make net-zero possible while we continue to deplete our fossil fuels reserves. We must not rely on CCS and CDR too much.

Carbon capture would weaken the reason for environmentally motivated governments to stop burning fossil fuels in the first place. This is great insofar as it reduces damages from climate change. But it could significantly increase the risk that we keep burning fossil fuels indefinitely, using up the easily accessible resources and undermining the prospects for recovery in the event of civilisational collapse.

Here’s to coal: once essential, now harmful. If we keep it in the ground, one day it could enable humanity to rise from the ashes of catastrophe to flourish once again.

Dig into these:

Pick up a copy of What We Owe the Future. Despite all the talk about gloomy topics like extinction and the end of civilization, it is an uplifting read, with a perspective sorely missing from public discourse.

For good measure, here’s a case against longtermism from within the effective altruism (EA) movement.

Out of the ashes takes an in-depth look at what it would take for civilization to re-industrialize.

Here’s everything you ever wanted to know about coal