The latest news from Brazil is great news for the climate

The return of Brazil to the world stage with a prominent climate agenda is one of the best things to happen in 2022

Never let anyone tell you that it doesn’t matter who you vote for.

In a year filled with extreme climate events of a sign-of-what’s-to-come kind, there have also been positive developments as political leaders around the world are finally starting to take meaningful action to combat the climate crisis by deploying lots of investment to decarbonize the world economy.

And last Sunday there was more good news: on October 30, Brazil voted to bring the administration of Jair Bolsonaro, a climate denier president, to an end after just one term. In his place, Brazilians chose to bring back to power former president Lula who between 2003 and 2010 oversaw a 72% drop in deforestation.

The vote was won by the narrowest margin in history and Brazilians remain deeply divided. And yet I view this election as an absolute triumph for democracies everywhere. My post script further down explains why I think that.

What has been happening in Brazil?

From 2019, Bolsonaro’s administration has unapologetically prioritized expansion of land use for cattle and agriculture over conservation, looking the other way as illegal land occupations and wildfires grow in scope and scale. And that has been very bad indeed for the Amazon forest. Environment protection agencies have been hollowed out. A head scientist who reported satellite data contradicting the president was fired. Devastation of the Amazon climbed over 70% to levels not seen in 15 years. All evidence suggests that the trend would have continued had the sitting president been re-elected.

Over the past four years there has not been any serious political discourse surrounding climate change in Brazil. Anti-environment policies have damaged the very industries they intend to support. Until last Sunday, Brazil seemed to have gladly jumped aboard the slow-moving anti-democratic bandwagon and had effectively gone into voluntary isolation, earning a near pariah status in the world stage.

The situation in the Amazon region is an extremely intricate and delicate problem that Brazil has been struggling with for many decades. Analyses by foreign media seldom reflect the nuances, with the issue usually presented as one of environmental policy only. While that is certainly a relevant part of the equation, there are complications as the issue is unpacked, such as deep-seated grievances between groups fighting for their livelihoods.

On one hand there are land developers seeking more real estate for mining, logging, and cattle farming with demand rapidly increasing as the country develops and the world wants more meat. On the other, native tribes with support from environmental and religious leaders are witnessing the forest, and the communities that rely on it to survive, rapidly shrink. The first group has immense political power and is a key constituency of Bolsonaro. The second group, not so much.

The tension between the two sides is constant and very often things gets very violent. Assassinations of journalists and activists who dare get too involved are not uncommon. Violence against native Brazilians is growing, by 48% in 2021 alone, fueled by the president’s rhetoric.

While Brazil has an environment protection agency that strictly regulates land development and protected areas, local and federal authorities can sometimes take a laissez-faire approach. Corruption in the region is endemic and many administrations prefer not to get involved with this thorny issue if they can help it. So authorities look the other way as illegal wildfires proliferate and people take matters into their own hands.

This opinion piece from the New York Times does a reasonable job of summarizing what is at stake:

Why does this all matter?

Many reasons:

Clearly the conflicts I describe above need to be resolved if people in that part of the world are to ever live in peace.

The devastation of this amazing ecosystem is just plain bad.

The same land use pressures are already creating a similar tragedy in another important wild ecosystem in Brazil. The Pantanal is much smaller and less well known internationally than the Amazon, but it harbors just as much wildlife diversity, it is more vulnerable, and it is also being burned.

And as it more specifically relates to the climate crisis:

Amazon forest dieback has been identified as one of the climate tipping points we are close to reaching. That would be bad.

Trees are carbon storage devices. As they burn to make way for land use, the carbon is released back into the atmosphere.

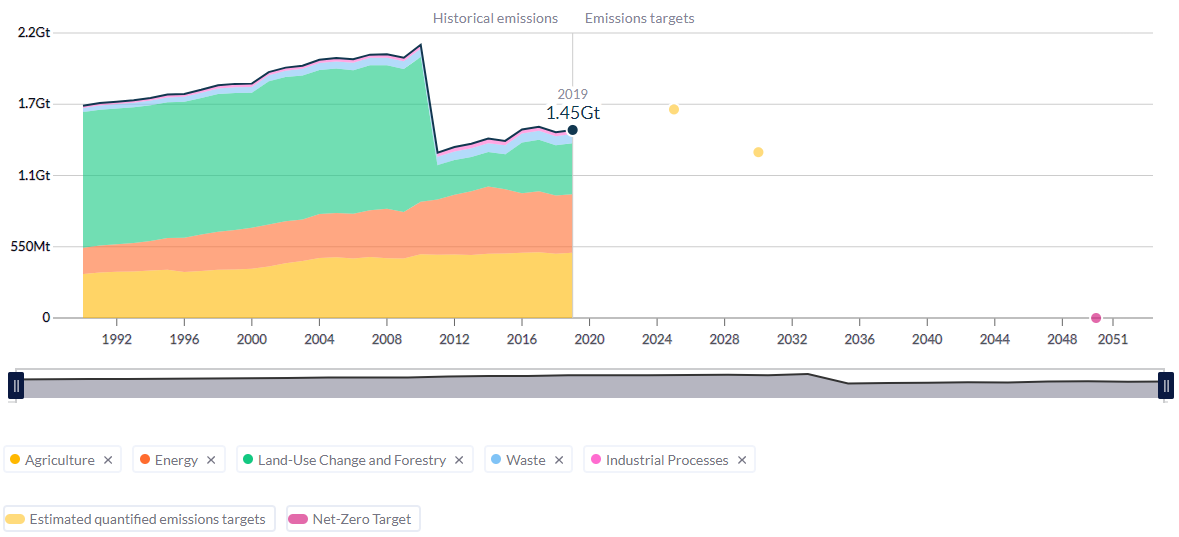

Close to one third of Brazil’s emissions come from deforestation. As the seventh largest emitter of CO2 in the world, stopping illegal fires would be a very big deal.

Will anything really change for the better?

That is anyone’s guess, but I find three things encouraging:

Lula’s first administration has a track record of significantly reducing deforestation. That was partly due to the creation (and enforcement) of new preservation areas, but also due to some skill in managing the conflict between agribusiness and native peoples. In his last victory speech he claimed it is “possible to create wealth without destroying the environment.” My hopeful interpretation: it is a signal that the government will strive to protect the Amazon and its communities without neglecting the legitimate needs of farmers agribusiness.

The new president has been making the right noises regarding investments in a green economy. His speech also points to a “zero deforestation” goal. Sure, that might be a tad too ambitious, but it sends a clear message to the world that the administration will mean business. There is already some indication that other countries are once again willing to help.

I was surprised to learn that Brazil’s energy grid is one of the cleanest in the world, with 84% of electricity already coming from renewables (in the 70s there were large investments in hydro power.) That puts Brazil in an enviable position amongst large economies, with a relatively small portion of the grid left to decarbonize. Brazil has the potential to seize the moment to take center stage in the global path to net zero, since a big drop in deforestation would significantly bring down emissions (agriculture and steel being the other big ticket items.)

The proof will of course be in the pudding. But the massively positive shift in the public messaging and climate policy ambitions now coming from Brazil cannot be denied.

In making a narrow but clear democratic decision, Brazilians have owned up to our responsibility to the world as the main caretaker of the largest forest in the planet. We are saying to the world that we understand its importance and once again commit to taking that responsibility seriously, as well as having a desire to show leadership in clean energy generation and sustainable economic development.

Welcome back to the world stage, Brazil. We've missed you.

Now bear with me as I take a moment to step away from climate matters to pay a tribute to Brazilian democracy.

Here is how last Sunday went.

The entire country, and a divided society, woke up to dress up colorfully, don flags and banners of their favorite candidate, and march to the polls to peacefully cast a vote. There is no early voting or absentee ballot in Brazil. And yet, turnout was far higher than in most modern democracies at 80%. There were more than 124 million voters, from a few remote tribes in the Amazon to 300,000 Brazilians living abroad. Free public transportation was provided across the country. The voting sites were well organized and the experience was safe, simple, and swift. Almost every single person cast their vote on a secure electronic voting machine that can tally up the results and transmit them to HQ in Brasília on a dedicated link mere minutes after voting is complete. Less than three hours after polls closed, more than 98% of votes had been counted and the winner officially announced. Despite the very narrow margin and deep wounds yet to be healed, the country could start moving on from elections to daily life, either celebrating or grieving the results, whatever the case may be. But everyone had certainty of the outcome by the time the kids were being put to bed.

Despite years of a campaign by the sitting president to discredit the electoral process, there remained no opportunity for the loser to question the results: all the institutions including Congress and the Judiciary, as well as political leaders of all party affiliations came forward within minutes of results being announced to declare that the election had been free and fair, and to congratulate the winner. The international community followed suit with all major countries quickly recognizing the outcome.

All of it happened in just one day.

Plenty of challenges remain for the incoming administration. And there are many reasons to be skeptical of the new leader who will rightly face fierce opposition and scrutiny (quite often from me.) But for now, I am allowing myself to show a little patriotism and marvel at the inclusiveness and efficiency and beauty of Brazilian elections as a model to the world.

Edit 5 Nov: happy to see the New York Times publishing an article making the same point I make above.